Andrew Kaul is a Restoration Ecology Post-doc in the Center for Conservation and Sustainable Development working with Matthew Albrecht at the Missouri Botanical Garden, and Michael Barash is a junior Biology major at Washington University in St. Louis. Here they describe Michael’s undergraduate research on commercial native seed availability for woodland restoration.

One of the largest barriers to restoration of degraded terrestrial habitats is availability of seed for use in reintroduction of desirable native plant species. Over the past few decades, the industry of native plant seed production has grown rapidly, but most native species in the US (and globally) are still not commercially available, and there can be strong biases in which types of species tend to be selected by seed producers.

In ecological parlance, a “species pool” represents all of the species which can colonize and occupy a certain region. Not all of the species in a regional species pool are available commercially, which is how many restoration practitioners acquire seeds, so the subset of species pool that contains only the species that are commercially available in a given region is sometimes called the “restoration species pool”.

For most ecosystems around the world, it is not well documented what proportion of the species pool is commercially available, and why these species have been selected for commercial trade. The few studies that have been conducted on commercial seed availability for restoration have found consistently that herbaceous (rather than woody) and rare species (rather than common ones) are less likely to be available, and there are strong taxonomic biases in which plant families are more represented. In the US, these studies have focused on open-canopy habitats with few trees, such as grasslands, rather than on more closed-canopy systems like woodlands and forests.

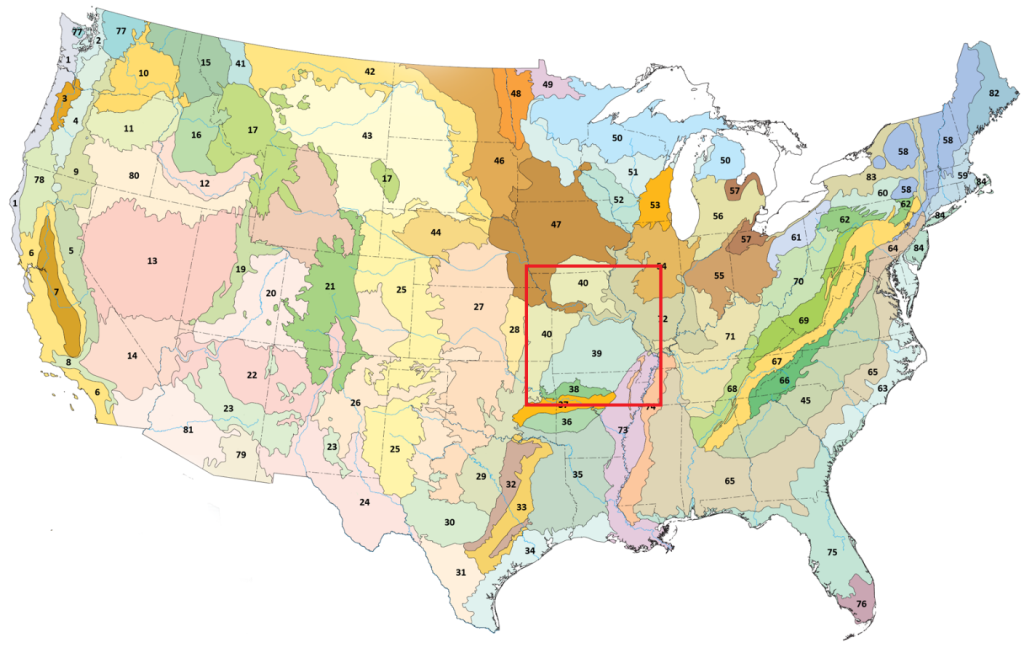

To address this information gap, we assessed the capacity of the native seed industry to support ecological restoration across terrestrial habitats in the Ozark region of the midcontinent USA. The use of seed additions to accelerate recovery of plant diversity in Ozark woodlands and forests is not well studied, and little information is available on how to best select species for reintroduction from seed. The specific goals of this project were to:

1) Identify the species pool of native herbaceous (non-woody) vascular plants appropriate for restoration of glades, woodlands, and forests in the Ozark Highlands;

2) Define the restoration species pool by identifying which of these species are commercially available;

3) Quantify biases in this restoration species pool with respect to growth form, rarity, habitat affinity, and a few important functional traits;

4) Identify candidate species which are not available from seed vendors, but should be a priority for seed production due to their importance for Ozark habitats.

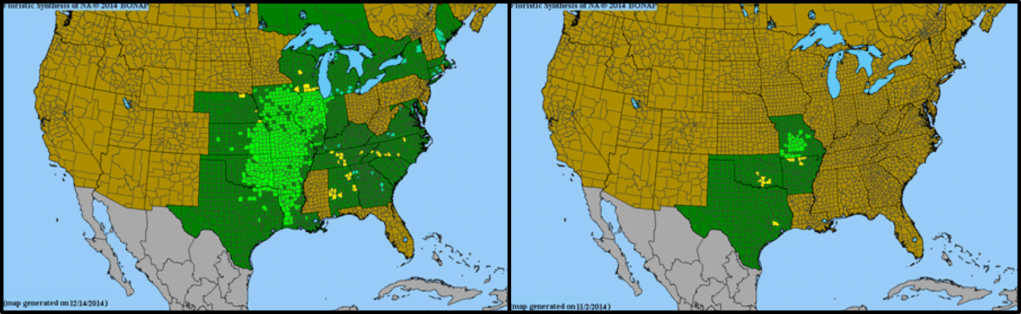

We began this project by developing a targeted species list of 1,178 herbaceous species native to upland habitats in the Ozark region, based on existing datasets from the Ecological Checklist of the Missouri Flora, the Flora of Missouri, and the Biota of North America Program (BONAP).

We predicted there would be selection, implicit or explicitly, by seed producers for species based on their growth form, conservatism score wetness rating, rarity, and functional traits. Each species’ physiognomy (growth form), conservatism score (that is, sensitivity to disturbance), and wetness ratings (a type of habitat affinity) were included in the Missouri Checklist. For each species in our pool, we compiled data on two measures of rarity including a qualitative measure – the official Missouri State conservation ranking, and a quantitative measure – the range size of the species in the US, as measured by the number counties in the nation where there have been recorded occurrences in the BONAP database. We compiled trait data on height of adult plants, and bloom timing and duration from species descriptions in the Flora of Missouri. For each grass species, we compiled data on photosynthetic pathway from published literature.

We made predictions that species with certain growth strategies, traits, range sizes, and habitat preferences would be under- or over-represented in the pool of species produced by seed vendors. We predicted that compared to other growth forms, perennial forbs would be over-represented in the restoration species pool because the aesthetic value of restoration projects is often a high priority, and perennial forbs with their big flowers, are “showier” and will return year after year. Similarly, taller species, and those with a longer bloom period may be selected preferentially because their blooms are more noticeable. We expected that species which have a smaller range or are not abundant in sites where they do occur are less likely to be in demand by restoration practitioners, so are less likely to be commercially available. Based on this pattern we expected species with a lower conservatism score, larger range size, and higher conservation rank (less concern for conservation) to be more commonly produced by seed vendors.

The cottage seed industry for prairie plants has grown especially rapidly in recent years, so we expected that species which are generally found in more open habitats like glades, prairies, and savannas, would more likely to have been selected by at least one producer than the species which occur mostly in shady habitats like woodlands and forests. Similarly, since open habitats tend to have drier soils than shaded ones, we predicted there may be a bias toward species with a higher (drier) wetness rating. Many grass species that grow in open habitats have evolved a more efficient way of conducting photosynthesis under hot sunny conditions. There are fewer of these “warm-season” grasses than “cool-season” ones, but we predict that proportionally more warm-season grasses will be commercially available, because they are common in the prairie seed market.

In order to test these predictions, we needed to compile information on which species in our pool are available from seed vendors. We identified ten seed vendors that are likely potential sources of seed materials for species native to the Ozark Highlands. These include five seed vendors within Missouri, four large regional seed vendors located in Iowa, Minnesota, and Kentucky, and one very large seed vendor that produces seed for regions all across all the US. We were able to get information on which species each vendor produces from their website, or if they did not have a website, then through personal communication. Many vendors sell a combination of seeds and potted plants, with most species only being available in one form or the other. For this study, we were only interested in seed products because restoration of herbaceous communities through seed additions is the most common and affordable approach.

Based on preliminary analyses, we found that 501 (43%) species were commercially available from at least one vendor. We found the strongest trends supporting the prediction that species differ in their likelihood of commercial availability based on physiognomy or “growth form”. Perennial species were twice as likely to be available as shorter-lived annual or biennial species, and as predicted, forbs were better represented in seed vendor catalogues than grasses or sedges.

We predicted that more common species would be better represented in the restoration species pool and our results somewhat support this prediction. Conservatism scores are assigned to species by expert botanists in each region, so they reflect how rare and how disturbance tolerant species are within local areas. In the US, these scores are often assigned at the state level. In order to avoid over-interpreting these designations, we binned scores into three groups including ruderal (0-3), matrix (4-6), and conservative (7-10) for use in our analysis. We found that “matrix” species with middling conservatism scores were more likely to be available than conservative or ruderal species. This may be because ruderal species can be somewhat weedy and may be expected to recruit into restored areas as volunteers. And on the other hand, highly conservative species may be difficult to grow for seed production, or have a small range, and thus limited restoration potential or demand. The state of Missouri has designations for the conservation concern of all native species. We found that species classified as “vulnerable” (S3), “imperiled” (S2), or “critically imperiled” (S1) were less likely to be available from seed vendors, as species classified as “secure” (S5) or “apparently secure” (S4). And finally, as predicted, we found that species with larger ranges are more likely to be commercially available.

We expected species which mostly occur in open habitats with little tree cover to be more likely to be commercially available. We classified each species as belonging to one of three habitat affinity groups, being an open habitat specialist, closed habit specialist, or a generalist. We found no bias in species availability based on habitat affinity or based on the wetness rating for Missouri. Based on the prediction that the prairie-focused seed market would promote availability of warm-season grasses, we thought they would have greater proportional representation in the seed market, but we also did not find evidence for that prediction. Warm and cool season grasses were equally likely to be available, with about a third of all species belonging to each group being available.

Traits of species may also contribute to seed vendors’ interest in propagating them. We found evidence that within perennial wildflowers (forbs), species with a taller maximum height are more likely to be available. We also predicted that species with a longer potential bloom period would be better represented in the seed market, but surprisingly our data shows a negative relationship, where species that can bloom for many months are less represented in the restoration species pool. This pattern may be driven by differences between functional groups or plant families and deserves further investigation.

The final goal of this project was to identify candidate species to recommend to seed producers as valuable for restoration potential. We identified such species based on the highly detailed descriptions provided in a keystone reference for this region, Paul Nelson’s The Terrestrial Natural Communities of Missouri (2005). This book describes the geologic, climatic, and natural features of natural community types in Missouri. We only considered habitats within the broad designations of forests, woodlands, savannas, prairies, and glades, and we narrowed our focus to only habitat types that occur within the Ozark Ecoregion. For each of these 37 Ozark habitats, this reference provides lists of plant species that are “dominant”, “characteristic”, or “restricted” to that habitat. We propose that a good starting place in assessing the capacity of the native seed industry to support ecological restoration across terrestrial habitats in the Ozark region is to examine whether all of the “dominant” plant species in habitats within the Ozarks are available from vendors. Of the 120 species identified by Nelson as “dominant” in Ozark habitats, 80 of them (66%) were commercially available. This is encouraging, since it is higher than the overall availability rate of 43%, however there are still 40 species which would be difficult for restoration practitioners to acquire without hand collecting from wild populations. This highlights how biases in the restoration species pool could potentially make assembling a high-quality seed mix more difficult, if the species for sale represent those which are easiest to cultivate, rather than being the ones which have the most biological significance to restoration.

Here, we are only scratching the surface in terms of identifying ways in which the seed production industry may inadvertently be biasing the restoration species pool and consequently the diversity and composition of restored plant communities. In the future we recommend continued collaboration between seed producers, restoration practitioners, and conservation scientists, to identify the limitations of available seed stocks and better align supply and demand for native seeds. Most seed vendors do not label products at taxonomic designations below the species level. However, conservation goals are sometimes identified for subspecies or varieties. The extent to which these taxa are commercially available is difficult to assess. Additionally, many restoration projects call for seed from a local provenance, but obtaining information on ecotypes of native seed lots from vendors can be difficult. While nearly 40% of our species pool for restoration projects in the Ozark Highlands are commercially available, the proportion of those species that are available from an Ozark ecotype is likely much lower.

We are currently preparing this project for publication. If you are interested in learning more, or have any questions, feel free to email Andrew (akaul@mobot.org).