Estefania Fernandez is a masters student at the University of Montpellier, France. She spent the past six months working with scientists in the Center for Conservation and Sustainable Development on a tropical forest restoration experiment in southern Costa Rica.

Costa Rica is one of the world’s most biodiverse countries, hosting 4% of flowering plant species in an area representing only 0.03% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface. With a large diversity of ecosystems, ranging from mangroves to cloud forests, Costa Rica hosts a unique family of (almost exclusively) Neotropical plants: the Bromeliaceae, commonly called bromeliads. With their colorful inflorescences and strikingly patterned leaves, numerous bromeliads are cultivated around the world for their ornamental value. Less is known, however, about their ecology in tropical ecosystems, particularly in regenerating forests.

Many of the so-called “tank bromeliads” are epiphytes, meaning that they grow non-parasitically on other plants. These bromeliads have ample rosettes of overlapping leaves, capable of holding considerable amounts of water. These water tanks keep them hydrated, and plant detritus that accumulates in these structures also provides bromeliads with nutrients. Arthropods take refuge in bromeliad rosettes, and consequently these plants attract mammals and birds seeking prey. Mutualistic ants build their nests in bromeliad rhizospheres, or root zones, and frogs lay eggs in the tanks. When sufficiently numerous in tree canopies, bromeliads can stabilize local temperature and humidity.

Despite these important ecological roles, vascular epiphytes like bromeliads are often scarce in regenerating tropical forests. Their recovery could be slowed by limited seed dispersal or by a lack of suitable recruitment sites. One way to overcome dispersal limitation is to transplant individuals. In our study area in southern Costa Rica, transplanting bromeliads is relatively simple because they are easily found on fallen tree branches in the old growth forest reserve at Las Cruces Biological Station. We hypothesized that transplanting bromeliads from the old growth forest into 10-year old forest restoration sites would buffer local temperatures and increase arthropod abundance and diversity compared to bare, control branches.

To test our hypothesis, we transplanted 120 bromeliads into three restoration sites in southern Costa Rica. The restoration sites are part of the Islas Project, an NSF-funded restoration experiment led by Drs. Karen Holl and Rakan Zahawi. Bromeliads were sterilized and attached to tree branches in the restoration sites with twine. Each day, we measured the microsite temperature on branches with and without transplanted bromeliads, as well as ambient temperature in the nearby air. To characterize arthropod colonization, we extracted and identified arthropods (to order) from transplanted bromeliads after two and three weeks.

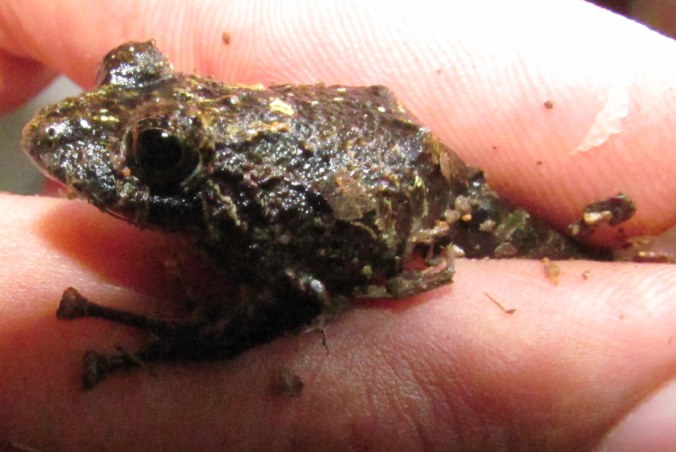

We found that transplanted bromeliads decreased local temperatures on tree branches, creating a less stressful microclimate for other organisms. Bromeliads also facilitated arthropods; transplanted bromeliads were quickly colonized, especially by ants. We also observed small frogs inside of some bromeliad tanks, but none on the bare branches where we did not transplant bromeliads.

We found this frog (Craugastor stejnegerianus) in a small Catopsis sessiliflora tank. (Photo courtesy of Dave Janas)

Our observations suggest that bromeliad transplantation can buffer microclimates and create useful structures for invertebrates. If so, this method could improve restoration outcomes for canopy flora and fauna. Given that this experiment was conducted over a single field season, it is still an open question whether transplanted bromeliads will survive over longer time periods. It will also be important to learn whether transplanted bromeliads will facilitate colonization by other epiphytic plants. We did find some evidence of this as ferns were already growing in several bromeliads’ rhizospheres after two months.