James and Thibaud Aronson describe the natural and cultural context of a little-known area of northern Colombia, home to the Wayuu people and a microcosm of arid lands worldwide.

Colombia is one of the world’s seventeen megadiverse countries. In a few hours of travel, one can go from the sweltering Amazonian lowlands to the snow-capped peaks of the Andes. It even has a true desert, a small peninsula called la Guajira, shared with Venezuela, which constitutes the northernmost point of South America.

For most of the last 50 years, the Guajira was notoriously dangerous, principally because of drug trafficking, but things have improved in recent years. We traveled there last month, shortly after the first big rains the region had received in several years. And we found that it’s a poignant example of the plight of drylands globally and their peoples.

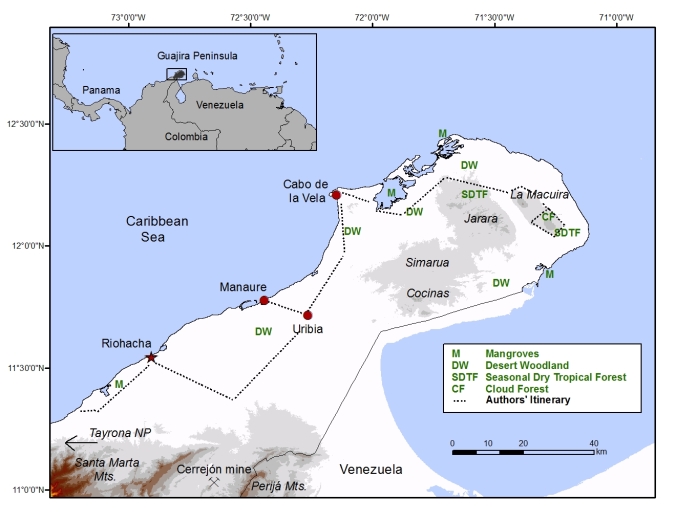

The Guajira peninsula, in northern Colombia, including the authors’ itinerary.

Our trip actually began in Panama, which was part of Colombia until 1903. While much smaller, Panama is also a country of contrasts. Much of the Pacific coast used to be covered in seasonally dry tropical forest, and some fragments persist today in and around Panama City itself, while the forests of the Caribbean slope, a mere 50 km away, are much wetter. A curious switch occurs near the Colombian border, where the wet forests then extend down the Pacific coast of Colombia and Ecuador – the famous Chocó-Darien rainforest, one of the wettest and most diverse tropical forests on Earth.

Meanwhile, the seasonally dry forests continue along the 1,000 km long Caribbean coast of Colombia and give way to semi-desert and then true desert (annual rainfall < 250 mm), lined by a coast with mangrove forests, and a series of lagoons and bays where flamingos and ibises add a shock of color.

Mangroves in Bahia Hundita, Alta Guajira, showing desert woodland with tree cacti (Stenocereus griseus) and various legume trees growing on the sandstone bluffs in the background.

Roseate spoonbills, great egrets, and a white ibis sharing a coastal wetland near Uribia.

As if this wasn’t enough contrast, halfway along the Caribbean coast rises the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia’s tallest mountain range, reaching 5,700 meters (18,700 feet) above sea level at the highest peak. It takes only about two hours to drive from its foothills, where toucans and monkeys chatter in the majestic trees, to Riohacha, the gateway to the desert.

A brown-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus) hanging by one arm in a Cecropia tree in Tayrona National Park, at the base of the Santa Marta mountains.

Alta Guajira’s desert trees and woodlands

The Alta Guajira is arid indeed, but it hosts trees, remarkable both in their exuberant diversity and their abundance, considering the high temperatures and meager rainfall. We saw what we consider true desert canopies, such as we have described in other posts. However, no desert flora exists in isolation, and indeed the kinship to the ecosystem type known as Seasonal Dry Tropical Forest (SDTF; see map above) seems to be strong.

The dominant trees of the Guajira are species of Prosopis, Caesalpinia, Vachellia (formerly part of Acacia s.l.), Parkinsonia and other legume genera, accompanied by Bursera, Capparis relatives, Bignoniaceae, and other species common in the dry forests of Central and South America, and 3 kinds of tree cacti (Stenocereus, Pilocereus, and Pereskia), growing close together, often covered in climbing vines. In particular, it was interesting to see bona fide desert woodlands dominated by two well-known legume trees, Prosopis juliflora and Vachellia farnesiana, which are widespread and often strongly invasive in other parts of the world, but not here! Fascinating biogeographical and ecological questions abound in this poorly explored region, many of which are relevant to conservation and restoration.

Regarding landscape ecology in the region, the vegetation is curiously like a patchwork, alternating between dense desert woodlands, nearly pure tree cacti stands, sometimes with a dense grass cover, and sometimes not, and frequent saline flats where nothing grows. In our opinion, the human element, namely land and resource use history, is paramount to understanding what one sees when travelling here and trying to ‘read’ the landscapes.

Mixed patch of tree cacti and spiny legume trees with a surprising amount of grass understory. Elsewhere under similar stands, for no clear reason, there is no grass cover at all.

A track of the Alta Guajira, near Nazareth, at the base of the Macuira hills where the notorious Prosopis juliflora, known in Colombia as Trupillo, is so exuberant and long-lived it forms a natural tunnel above this track.

Prosopis juliflora colonizes newly exposed beach dunes, in areas where the shoreline is receding. Here, at Camarones, it occurs alongside Calotropis procera, a woody weed of the Apocynaceae known in English as giant milkweed, and familiar throughout the Caribbean islands, the Middle East and drylands of Africa. It survives because of its toxic milky latex where most other plants get eaten out by livestock.

Other standouts are the beautiful Palo de Brasil, Haematoxylum brasiletto, with its unusual fluted trunks and Pereskia guamacho, an enigmatic ‘primitive’ tree cactus with true leaves and one of the most exquisite tasting fruits we know. This is one of the least well-known but most intriguing of all desert trees to our minds.

Typical landscape of the northern Guajira desert woodlands, with an even-aged stand of one of the several neotropical legume trees known as Brazilwood: Haematoxylum brasiletto, or Palo de Brasil in Spanish.

Despite those common names, this species is in fact only found wild along Caribbean coastlines from Colombia and Venezeula, all the way north to both coasts of Mexico. The scientific name is thus a misnomer. The most famous Brazilwood tree is another legume, Paubrasilia echinata (= Caesalpinia echinata) that once grew abundantly along the Atlantic coast of Brazil, as a large tree with a massive trunk, reaching up to 15 meters tall. Today, it’s almost entirely gone in the wild, and mostly planted in gardens and along roadsides. It was prized for the bright red dye obtained from the resin that oozes from cut branches or trunks. The dye was widely used by textile weavers in the Americas and Europe in the 17th-19th centuries. The tree also provided the wood of choice for high quality bows for stringed instruments and was widely used for furniture making as well. So important was its economic value that the country was named after it, originally Terra do Brasil (Land of the Brazilwood), later shortened to Brazil. Recently it was designated as sole member of a new genus, as part of a comprehensive revision of the entire genus Caesalpinia, carried out by an international team of experts.

It’s curious that H. brasiletto bears the same common name as P. echinata, since the two trees are nothing alike, apart from their red sap and heartwood. Little literature exists for H. brasiletto, and we are embarking on some detective work to shed some light on this puzzle. We go into detail as these are both relatively fast-growing trees with great economic as well as ecological value. They would both be excellent candidates for inclusion in ecological restoration work and are both in dire need of conservation efforts.

Wayuu: Alta Guajira’s Indigenous People

This desert also hosts a fairly large human population. The Guajira is the home of the Wayuu, Colombia’s largest surviving Indigenous group and, along with the Navajo, one of the last desert-dwelling peoples in the New World. These fiercely independent people, organized in 17 matrilineal clans, were never subjugated by the Spanish, and even today the Guajira region functions mostly in isolation from the rest of the country. As we were heading well off the beaten track, we needed a guide, a 4 x 4 jeep in good condition, and a skilled driver to navigate the meandering and unmarked desert paths.

Despite an ancient history of human presence, and some periods of intensive exploitation and intervention (such as a pearl harvesting boom that took place soon after European explorers arrived), the ecological condition of the region at the landscape scale is remarkably good. Indeed, apart from the salt works in the small town of Manaure, which produce two thirds of Colombia’s salt, and El Cerrejón, South America’s largest open-pit coal mine, in the south of the Guajira, there is no major industry.

Typical traditional salt works at Manaure worked by hand by local men and women just as they have for generations.

And the isolated people who dwell here – fishermen, shepherds, and weavers – are right out of a Gabriel García Márquez story. Indeed the author, most famous for One Hundred Years of Solitude, grew up on Colombia’s northern coast, speaking both Spanish and the Wayuu language, Wayuunaiki. As we traveled deeper into the desert, we traversed small settlements with simple houses made of wood and yards surrounded by tree cacti hedges.

The Wayuu village of Boca de Camarones, in the south of the Guajira peninsula, showing the living hedgerows of columnar cacti produced from tall stanchions. In the background, surrounding the homes, are Trupillos, and good specimens of Dividivi Libidibia coriaria (formerly called Caesalpinia coriaria).

This third caesalpinoid legume tree, closely related to the two Brazilwoods mentioned above, is the source of another lovely red dye, derived in this case from its pods. Until recently, there was an annual festival in Camarones, in honor of this formerly major economic plant product. The tree was also used as an important source of tannins. Like Paubrasilia echinata, it deserves more ethnobotanical and biogeographical studies.

Here, as in many other arid lands, goats and sheep are important for the Wayuu people, as a source of food and social currency. For example bride price during arranged weddings, and gifts for guests attending vigils of important elders and healers, are paid to this day in heads of live goats or sheep. Historically, mules and donkeys were very common as well, but now they are increasingly replaced by motorcycles.

Small children following a flock of desert-hardy sheep in Boca de Camarones. The peaks of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta are visible in the background.

Crown jewel of the Alta Guajira

The crown jewel of this desert, its best kept secret, is the Serranía de la Macuira, a small mountain range (serranía meaning “small sierra” in Spanish) in the northeast of the peninsula. This miniature sky island is almost impossibly lush, thanks to moisture-bearing clouds that shroud its upper reaches. They feed streams that flow year-round, and sustain many kinds of trees that grow to well over 10 meters tall.

As one climbs the slopes of the Macuira, the humidity dramatically increases and the parched lowlands, with their desert woodlands, blend perceptibly into a seasonally dry tropical forest reminiscent of those we had seen in Panama. A little-known fact: seasonally dry tropical forests are the most endangered of all tropical forest types, and those in La Guajira are worthy of much greater research, conservation, and restoration.

Climbing higher still, the mid- and upper ranges of the Macuira seem like another world. Most astonishing of all, there is apparently an abrupt transition above 550 meters, and the higher reaches are covered in true cloud forest, with mosses, epiphytic orchids, tree ferns, and dozens of tree species that otherwise occur hundreds of kilometers away! This is probably the only place in the world where cloud forest is found less than 5 km from true desert. Fortunately – from a conservation point of view, but unfortunately for us – the upper peaks of all three peaks of the Macuira are sacred to the Wayuu, and completely off-limits, to native people and visitors alike. Try as we might, we were unable to get permission to hike up there.

Seasonally dry tropical forest on the northeastern facing slope of the Macuira, where precipitation is much higher than in the surrounding lowlands occupied by desert woodlands.

Even though the whole Macuira is officially protected as a national park, the reality is more complicated. While walking inside the park, we encountered recently cut trees, the ubiquitous goats, and even a Wayuu man hunting birds with a slingshot in broad daylight. The beautiful continuous tree canopy covering most of the slopes stands in stark contrast to the severely eroded, nearly bare hilltops, on which stand small Wayuu homesteads. Still, the presence of clear ecotones speaks to mostly healthy landscapes.

The severe erosion around a small Wayuu farm inside the Macuira National Park.

Alta Guajira’s ecological future

The pressures on the Guajira’s ecosystem health include a large mine (El Cerrejón, mentioned above), overgrazing by domestic livestock, and stark poverty facing the native people and more recent immigrants. But there are positive factors as well. There are progressive laws in Colombia related to ecological restoration. Moreover, since 2012, Colombia has a National Restoration and Rehabilitation Plan (pdf), as well as a Law of Remediation, which imposes large environmental offset payments from large-scale development projects (like hydroelectric dams) to underwrite conservation and restoration work. Moreover, the national park system, within its network of 56 protected areas, harbors populations of almost half of the 102 Indigenous peoples in the country, and in the case of Macuira, this is clearly not just a paper park idea.

Still, the national park (25,000 ha in size; officially designated in 1977), operates with a skeleton staff attempting to carry out an ambitious management plan (pdf) despite an insufficient budget. Staff and volunteers provide short tours to day-visitors, and maintain some fenced-off livestock exclosure plots, where they are studying natural regeneration. Daily interaction with the Wayuu living in the park appear to be harmonious, and indeed there is a clear sense that part of the Park’s mission is to restore and protect the Wayuu people’s natural and cultural heritage. Recently, the Instituto Humboldt, Colombia’s stellar national research institute, has established permanent plots in the Macuira range as part of a series of 17 plots including all the tropical dry forest types in Colombia. In the Macuira, this work is done in collaboration with botanists from the Universidad de Antioquia, in Medellin. Furthermore, researchers at Kew, the Smithsonian Institute, and many conservation NGOs are all developing collaborations with the Colombian government to explore and help the country move forward with green development. The Missouri Botanical Garden also has long-standing MoUs for joint research with 3 different institutions in Colombia, with bright prospects for deepening cooperation in the future.

Like many Indigenous peoples around the world, the Wayuu are at a crossroads. Their language and some of their traditions are still alive and well, but others have already faded. There are few legal sources of income in the harsh desert, the ancestral Wayuu land. How will they manage in the future? What can they do to adapt? Some, like our guide, José Luis, are trying to change mentalities, but they clearly need more help. As throughout Colombia, there is clear and urgent need to build on the alpha-level studies already underway, and move onto applied ecology, agroforestry and land management programs, including community-based restoration programs and ecotourism in conjunction with the national parks.

Our Wayuu guide José Luis Pushaina Epiayu (on the right) and Macuira park ranger Ricardo Brito Baez-Uriana (on the left), talking about birds with a local Wayuu family.